Bill Hanneman, 1927 - 2020

The name of Bill Hanneman has become something of a household word in the field of gemmology, but not from any conventional approach to the subject. He saw that for anyone wanting to study the subject, the traditional routes were expensive. This irked him to the extent that he set out to explore the field and devise gem testing tools which could let the user tackle the question of gem identification at a fraction of the cost, while enjoying a whole lot of fun in the process.

From his Californian niche as chief analytical chemist for Kaiser Alumina, Bill was always on the lookout for anything ‘New’, and at the time there was a rapid growth of gem fairs, mainly due to the activity craze of ‘Tumbling’ gemstones.

Visiting some of these events, Hanneman realised that few of the sellers had any idea exactly what they were selling. With a little swotting up of the literature, Bill developed a series of filters which could screen a whole display of gems, mainly bead necklaces, looking for intruders which showed a different filter response from neighbouring gems, and so was born the ‘Hanneman Bead Buyer’s & Parcel Picker’s Filter Set’. More filters were to follow over the years with the appearance of new gems, as was the case with tanzanite and the inevitable ‘Tanzanite Filter’.

As an aid to identification, Hanneman realised the significance of specific gravity, and understood the historic use of the beam balance (Westphal’s) to determine the property. His own innovation was an alternative beam (aluminium of course), two feet long. This was too lengthy for ease of posting, so, his bar was halved and bolted together by the user when needed - a typical Hanneman improvisation which was simple and inexpensive to solve a problem. The beam balance could never compare with the results from density determination by the method of hydrostatic weighing to three or even four decimal places, but by reproducing the procedure three times and taking the average, to two decimal places, it achieved its purpose. This was by reference to a set of density tables, which quickly narrowed down the identity possibilities to two or three at the most. Final identity was then achieved by turning to one or more other of his tools. There was not even any calculation required of the beam balance, as the specific gravity was read off directly from the scale which was glued to the bar.

My friendship with Bill Hanneman can perhaps be blamed on YAG (the synthetic yttrium aluminium garnet). The original material was developed in the 1960s for uses in industry as a laser. It was in the 1970s, that it was first seen as having a use in the gem trade, as its hardness and optical properties, when faceted, presented a diamondlike appearance. Its introduction into jewellery created an identification problem for the jeweller, as its refractive index of 1.83 was higher than the reach (RI 1.81) of the standard critical angle refractometer.

The April 1975 Journal of Gemmology carried an article on a ‘new electronic refractometer’ - the Gemeter. Hanneman appreciated the significance of the development, but recognised it was not in fact a refractometer. He also recognised that at nine inches in length, it was a bulky unit and saw that the whole conception could be miniatured into a small unit which would fit in the shirt pocket, and so was born the Jeweler’s Eye. With an eye to free publicity, Hanneman wrote the article ‘The role of reflectivity in gemmology’ for the Journal of Gemmology, April 1978. With an eye to sales, he modified the instrument as the “Diamond Eye’ designed to reach a more interested sector of the jewellery trade

Dr Hanneman understood the innate complement of the two optical properties, refraction and reflection, and proposed the introduction of a new optical property – reflective power, which he termed ‘Lustre units’.

The ‘Eye’ was reported in the UK journal “Retail Jeweller’ and caught my eye, especially as the designer was coming over to the UK to help launch his instrument. While in London, Dr. Hanneman visited the gem testing lab in Hatton garden (the first such institution in the world) and met with its director, Basil Anderson. They formed an immediate bond, as both were graduate chemists, apart from them each taking a liking to the other.

I travelled down to London to meet up with Bill Hanneman and his wife Margaret. Invited back to their room after dinner, Bill showed me a faceted gemstone he had acquired. Holding it to my eye ‘Visual Optics’ fashion, I observed on its low refractive index and dispersion similar to quartz , but the birefringence was superior to quartz. The low birefringence ruling out feldspar I suggested the stone might be a scapolite.

Hanneman was captivate by the procedure and accurate identification. I showed him the article “Visual Optics’ I had authored in the 1978 Journal of Gemmology. Hanneman proceeded back to the States where he authored a paper on the subject in the 1979 Lapidary Journal, ‘The Educated Eyeball’. This was the start of our friendship which was to last through the next 30 plus years, collaborating on various gemmological projects. As Bill developed new ideas, they were turned into simple-to-use gem testing instruments. This was accompanied by a small book, ‘Affordable Gemology’, which was to capture the imagination of many gemologists, veteran and newcomer worldwide.

Encouraged by Bill to pursue Visual Optics further, I constructed an air refractometer which could indicate an approximate refractive index and birefringence. Its usefulness was confounded by the varying pavilion facet angles. I turned to Bill and he responded with the breakthrough, The Hanneman/Hodgkinson refractometer - an instrument without any contact liquid requirement. While not possessing the acute accuracy of a critical angle refractometer, this was of little consequence, as the RI and birefringence could be measured, immaterial of the refractive index, which was the stumbling block of the standard refractometer. The readings recorded in degrees are then converted to refractive indices by reference to a booklet of tables.

An additional bonus was that for the first time, the dispersion of a gemstone could be measured. The accuracy was approximate, but this was offset by the fact that, with the RI, birefringence and dispersion indices acquired, the identity invariably emerged by turning to a standard set of tables.

However the real bonus was Bill’s introduction of the B/D ratio. This is achieved by dividing the birefringence by the dispersion. As the new H/H refractometer could measure dispersion approximately, the B/D ratio was observed by simply looking at the stone via the Visual Optics procedure, and once the observer noticed any doubling of images, primary or secondary, the stone could then be axially manoeuvred to reach the maximum separation (birefringence ) of the doubled image. This B/D ratio could then be used as a completely new optical index for the gem tester to employ without any instruments whatsoever - provided the moon was out, or a candle in the vicinity as light source. Without such, a penlight provides another of Bill’s pocket aids – fitted with a simple plastic cap slit to provide a perfect light source for Visual Optics in any situation.

Bill Hanneman was in his element if he could find someone or something gemmological to argue about. A good example was the article in Gems and Gemology which set out a suggested new framework for the garnets. The optical properties proposed as the framework, were not to Hanneman’s liking, and he responded with his own garnet proposals. The Journals are not always co-operative with anything new and in exasperation, ‘The saga of identifying garnets’ was published, dedicated to the Scottish Gemmological Association, the year he was our keynote speaker. This included two pull out pages which folded to form a three-dimensional model he christened “the Rosetta stone of garnets”. That the book was dedicated to our Association was due to the fact that I had invited Bill to be keynote speaker at our annual conference and he was so captivated by the friendly reception he received from Scotland.

Another battle was fought with the mineralogical world which argued that there was no such mineral name as tourmaline. Hanneman responded with an onslaught on such a preposterous idea which was at loggerheads with all the gemmological literature. He argued that the ivory-towered mineralogists would sit on the fence of a name for any new gem find. Meantime, the gem trade needed to trade, and if they were to prosper, they needed a suitable name from day one. This way the name could be spread, samples sought and the market could continue to prosper. The two worlds collided, but the name tourmaline survives, as it is an established fact, apart from its eclectic pleasantness of sound on the ear – always a plus for business. And so we now have tanzanites, Paraiba tourmalines and tsavorites , the latter name finally accepted by the mineral world provided it was tsavolite, to suffix the name from lithos, the Greek for stone.

‘Affordable Gemology’ was yet another Hanneman gemological development which aimed to put the means of identifying a gemstone into the hands of anyone interested, without the precedence of spending much time and expenditure along the way. Such a journey is now one of exciting adventure. Once undertaken, the converted can follow the route as far as they need, by simultaneously studying the science of gemology through one or other of the Internationally recognised academic bodies, or even ultimately to a degree, as in Birmingham, and this from a standpoint of simply admiring a gemstone and wanting to know its name.

It was inevitable, that as the name was repeated, a crescendo built up of requests for Hanneman to give talks and demonstrations. From local lapidary clubs to The Tucson gem fair, Hanneman delivered a new laidback formula disseminating gemological information (often with tongue in cheek). Then the invites came from further afield: Canada, Europe and so the name became further publicised by its self propagator. This because Hanneman considered himself a ‘SOG’ – self ordained gemologist.

Hanneman was one of the few gemologists in the world to be awarded the Tony Bonanno award for contributions to gemological education. The photo below shows the recipient on the night of his investiture, alongside others who had received the award.

Some winners of the Tony Bonanno Award for Excellence in Gemology

From left: Al Gilbertson, Thom Underwood, John Koivula, Alan Hodgkinson, Antoinette

Matlins, Bill Hannman, Cigdem Lule, Dick Hughes, Richard Drucker, Stuart Robertson.

Other winners not in the photo include: Donna Hawrelko, Robert Weldon, Karl Schmetzer,

Christopher Smith, Alan Jobbins, Cap Beesley, Robert Crowningshield, Shane McClure,

James Shigley, Emmanuel Fritsch, John Emmett.

We are proud at the Scottish Gemmological Asociation to have welcomed nearly all the above as key speakers at our annual Scottish conference.

For all his scientific bent, Hanneman was also a stickler for the English language and the use of English in written or spoken form. This, when juxtaposed with gemological education, lead to the Hanneman award for contributions to gemological literature. Early recipients were Basil Anderson’s ‘Gem Testing’ and Richard Liddicoate’s ‘Handbook of Gem Identification’.

All the above was undertaken for the sheer satisfaction of promoting gemology with little thought of reward, as the talks were always undertaken without fee. Just as the Rosetta stone has lasted five thousand years, so Hanneman’s gemological legacy will live on, for how long, we shall have to wait and see!

Finally in his 90s, Bill Hanneman gave up his hold on life but his name and reputation live on gemmologically.

Written by Alan Hodgkinson

Bill and Alan

Eric Liddell Centre, located on the southside of Edinburgh at:

Map: 15 Morningside Rd, Edinburgh EH10 4DP.

It is just past the junction of Bruntsfield Place, Colinton Road and Morningside Road. Evening parking in this area usually presents no problems and the Centre is served by Lothian buses services 5, 11, 16, 23, 45.

If you would like to join us afterwards just for a coffee, a drink or something to eat, we will have a table booked at the nearby Cafe Grande.

Our Whitby and Castleton Trip

Gallery 1

Gallery 2

My Journey to Gemmology

A personal reminiscence by Harold Killingback

On 27th March 2020, I collapsed and was ambulanced to hospital where I was diagnosed Covid 19 positive. I was 95 years old and had Parkinson’s Disease so, by the law of averages, I should no longer exist. The “law of averages”, however, does not exist so here I am, one year on. A time for reflection.

My work pension was to become payable when I reached the age of 65. My employer changed this to 60 for new recruits and gave existing employees the offer to change to the new terms. Problem: fewer years of service so smaller pension but earlier retirement gave the opportunity to establish a new occupation. I wanted to learn silversmithing so accepted the offer. I was fortunate that evening classes in silversmithing and jewellery were available locally. Raised work fascinated me and my first piece was a simple beaker, Figure 1. It is hallmarked London 1975.

Silver provides wonderful reflections: the red of the velvet on which it lies and colour of the whisky (Scotch, of course) varies in intensity as the depth decreases and the outlines become a bit blurred! Most of the other students were making jewellery so I was able to look at the stones they were setting. Figure 2 shows a bowl I made (hallmark London 1990). It has 12 mm diameter synthetic sapphires in open settings. The idea is that light would be reflected from the inside of the bowl and up through the stones to provide a lively effect.

Star diopside fascinated me. I like the nearly black cabochons against the bright silver. The star has four rays, reminiscent of a cross when lit from a single source. I set some in a Communion Cup and Paten, Figure 3. It is Hallmarked London 1996. The stem is raised from a circular disk, producing a tall vase-like piece. The base is cut off and the stem flared to blend with the bowl which has been raised

from another disk. I left the stem as textured by the raising hammer, a reminder of the brutality of crucifixion. The bowl is smoothed by planishing but still presents myriads of plane surfaces, each reflecting the incident light. Hand raising produces so much life, missing from dead smooth commercial spinning and stoning. In 2017 I had the honour of presenting it in Leicester Cathedral to

the newly consecrated Bishop of Loughborough. (See Gems & Jewellery Spring/2018/Vol 87/No 1.)

My most ambitious work, Figure 4, is inspired by the Viking burial ships, particularly the graceful sweep of the undecorated stem and stern posts of the Gokstad ship. The cup nests in three prows and these are borne up by bursting waves. Hallmark London 1997.

My interest in gemmology led me to study it seriously, so silversmithing went into abeyance. I got my Diploma and became an FGA in 2002. Since then, I have developed my interest in asterism and chatoyancy, and various other aspects. Most recently (see Journal of Gemmology Vol 36/No 7/2019) I have pointed out that the maximum separation angle between the rays in uniaxial doubly refractive crystals is not dependant on the difference between the highest and the lowest refractive indices (sometimes called the birefringence) but on the ratio between them. I have suggested that teaching should be corrected accordingly. The matter is sub judice.

Meanwhile, one thing I am certain of is that keeping my brain working, together with physical activity, has been of vital importance in combatting the effects of aging, Parkinson’s, the weather and Covid 19!

The Albert, Prince Albert and the Modern Primitives

Article by Alistir Tait

Once upon a time, a gentleman about town, should he require knowledge of the time, would not have referred to his mobile or cellular phone, as we do today. He would have pulled back his cuff and read the time in a digital or analogue manner according to the watch on his wrist. In earlier days watches were less evolved, larger and more fragile, they were carried in pockets. During the early decades of the nineteenth century a gentleman would secure his pocket watch in a fob pocket at the waist of his breeches, the watch attached to a fob which hung jauntily out of the pocket and assisted safe and easy handling whist also being an item of beauty and value in its own right.

However, by the mid-nineteenth century men were modernising their dress and adopting the fashion for trousers with waistcoats the style of which further evolved over the following decades. I am often asked how a pocket watch and chain should be worn with a waistcoat and suit. The answer is simply that there is not, and there never was, a standard or traditional practice in this regard. A perusal of old photographs, calling cards (carte de visite), daguerrotypes, contemporary fashion plates, portraits and trade catalogues bears this out.

For ladies there was the Albertine the Albertina and the Leontine, the later named after Leontine Fay a mid-nineteenth century French actress. There was the Langtry, celebrating Lily Langtry and other variations named after Empress Eugine, Maria Clotilde of Savoy and the Malthilde named after Princess Mathilde of France, amongst others. There were guard chains and chatelaines of a type very different to that of the 18th century and sold for both men and women. The terminology can be quite confusing. On examination there isn’t a lot of distinctive difference between many of these chains but for women they were generally shorter and more decorative than those for men. For gentlemen the most notable style was the Albert chain and a shorter version for ladies called a Victoria. In America these ‘vest chains’ were often sold as ‘Dickens chains’ Charles Dickens being at the height of his popularity in the US at that time. The Albert or Prince Albert chain is a moniker well know to us still today.

For the wealthy these were manufactured in gold, typically 9ct, 15ct and 18ct standards with 14ct gold popular in America. Sterling silver was much used and later platinum was often found on mostly finer chains to highlight alternating links. For the less affluent there was gold plate and nickel, although fewer of these survive due to their ephemeral nature. Likewise, recent high bullion prices and the demise of pocket watch wearing has led to many items ending up in the melting pot. There are also few survivors made from alternative materials such as jet and it’s imitations, braided silk or hair, either human or otherwise.

Regarding the origin of the name, there has been some degree of cultural misappropriation and there is a popular story often expressed in print relating to this, here we are going to encounter a very specialist jewellery niche. Particularly, amongst the body modification sub-culture it is strongly believed that in his twenties, Prince Albert had his penis pierced and attached to a length of chain so that it could be supported in tight trousers in an aesthetically pleasing way. There is a suggestion that he suffered from Peyronie’s disease and that the genital piercing was intended to help straighten his manhood. This arrangement is known as a Prince Albert. It consists of a ring-style piercing that extends along the underside of the glans from the urethral opening to where the glans meets the shaft of the penis. Dear friends, this is not a procedure to undertake lightly, healing time can take from 4 weeks to 6 months and infections are to be avoided and more particularly so in those times before penicillin.

Is the connection with Prince Albert true or is this a modern myth? That there was an interest in body piercing in Europe in the Victorian age is well known but how far back do we have to go to find an original or contemporary account of this tale? In the late 1960s and early 1970s there was a small group of individuals who identified themselves as the Modern Primitives, sometimes also known as Urban Primitives. They were associated with the hippy, punk, gay, motorcycle gangs and BDSM sub-culture of California at that time. Fakir Musafar, born Roland Loomis (1930-2018) an ex-advertising executive turned self-proclaimed shaman, took his new-age name from a nineteenth century Sufi who had spend eighteen years in meditation with daggers piercing his body. As Fakir Musafar, his life was consumed manipulating flesh in search of the spiritual transcendent and the transformative. He wanted to introduce modern society and middle class Californian urbanites to extreme body modifications inspired by anthropological studies of primitive tribes. He believed that these tribes in their simple and unsophisticated pre-colonial lives were more connected to the spiritual and that through extreme piercing and modification of the body we too could experience this enlightenment.

Modern Primitives (alternatively Urban Primitives) engage in body modification rituals inspired by the rites of passage, rituals or body ornamentation in what they perceive as primitive societies. The practices include body piercing as well as scarification, tattooing, play piercing (piercing for the sake of experiencing pain/pleasure rather than to create a permanent decoration), cutting, branding and more. Motivation for engaging in these varied procedures can be personal growth, a personal rite of passage, spiritual or sexual curiosity. The shortcoming of this movement is seen in the contrast between the modern purpose for these practices taken out of their original cultural contexts and therefore nullifying the authenticity that adherents search for.

Jim Ward (born 1941) was an important part of this group and he is considered the father of the extreme piercing movement in the modern world. He came to Los Angeles in 1973 with interests in tattooing and genital piercing and funded by Richard Simonton (1915-1979) he established a piercing studio – The Gauntlet. With no Western tradition to fall back, on he devised and established many of the piercing techniques used today. Simonton was a successful entrepreneur and businessman but had adopted the name Doug Malloy to protect his privacy. Around 1975 Malloy published a leaflet titled ‘Body & Genital Piercing in Brief’ which gave full play to his imagination and love of the fantastic. He wanted to give credence to these new practices by referring back to their historical application by earlier cultures and for this he created exotic origin stories to give integrity to specific piercing practices. On the Prince Albert he writes:

“The Prince Albert called a “dressing ring “ by the Victorian haberdashers was originally used to firmly secure the male genitals in either the right or left leg during that era’s craze for extremely tight crotch-binding trousers, thus minimising a man’s natural endowment. Legend has it that Prince Albert wore such a ring to retract his foreskin and thus keep his member sweet-smelling so as not to offend the Queen. Today its function is strictly erotic, providing the ultimate in sexual pleasure to men of both persuasions. Piercing is through the urethra at the base of the penis head. The procedure is quick, then pain minimal; the healing rapid; and the pleasure, lifelong.”

The legend of the Prince Albert cannot be reliable traced back before the leaflet of 1975. It is an urban myth, an origin myth in fact.

So, if this tale is a fiction, from where did the jewellery trade adopt the term a Prince Albert chain? In November 1843 Prince Albert visited several factories in Birmingham including some within the Jewellery Quarter. He was much impressed by Messrs Elkingtons, where he saw their new method of electro plating at their workshops. In 1845 the Quarter received royal approval when Queen Victoria and Prince Albert agreed to wear jewellery to the value of over 400 guineas, gifted to them from the jewellery merchants of Birmingham with the aim of promoting their products. According to Brewer’s Dictionary we learn: “When he (Prince Albert) went to Birmingham in 1849, he was presented by the jewellers of the town with such a chain, and the fashion took the public fancy.” The chain passes from the watch in the waistcoat pocket to a buttonhole of the waistcoat. This would now be called a single Albert. A carte de visite of the Prince Consort shows him wearing such a chain and after his death Queen Victoria wore it often in his memory.

Prince Albert died, age 42 in 1861 and Victoria in 1901 so we shall never know the secrets of the Royal boudoir but I think we have put an urban myth to rest. So, gentlemen whether you enjoy sporting an Albert or alternatively a Prince Albert, I hope you wear it with both pride and pleasure.

The Posy Ring

AN ARTICLE BY ALISTIR TAIT

We can make some general comments on the traditional matrimonial ring. The Western tradition of the wedding ring dates back, to at least, the ancient Romans and Greeks, the Romans believing that the fourth finger of the left hand contained a ‘vena amoris’ or ‘vein of love’ that led directly to the heart. In Christendom the wedding ring was considered a tangible proof of God’s blessing on the union of a man and a woman.

During the 1648-1660 Commonwealth the Puritans, in their boldness, attempted to abolish the wedding ring because of its associations with bishops and the ritual laid down in the Prayer Book but so strong was the feeling for it that they failed to convince public opinion.

Whether this ring constitutes a symbol of a woman as property of her husband I shall not consider but Samuel Johnson is infamously quoted as saying that a ring “is for the finger of a woman and the nose of a pig for bringing both into subjugation”. What is above doubt is that a betrothal ring is often the plainest of gold bands, a love token and gift of great symbolism and intimacy.

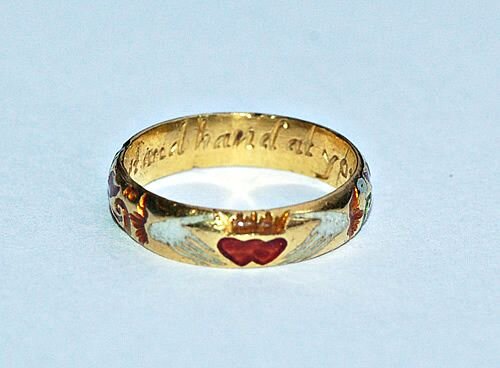

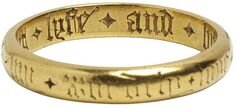

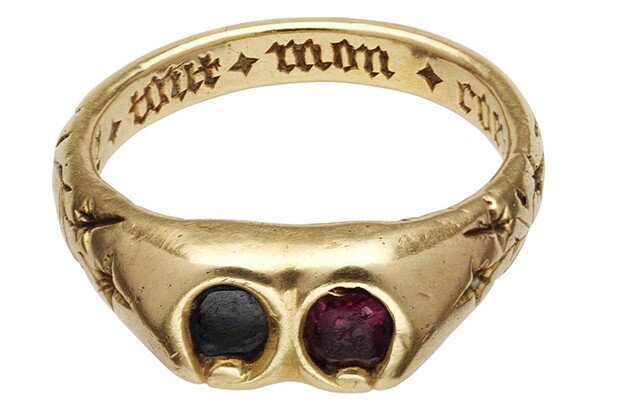

From the fourteenth century it was not uncommon for a betrothal ring to be embellished with a inscription typically on the outside of the ring. Often in Latin or French and the lettering blacked with niello. By the fifteenth century such an inscription was typically on the inside of the ring, known only to the wearer. Indeed, an inscription became commonplace and such was remarked upon in literature by Chaucer. These mottoes known as posies (posies/poesies) or little poems were usually in French (chançon ), for centuries the universal language of love.

Posy rings should not be confused with the tradition of floriography and the decorative floral patterns with which lovers rings have been embellished. More than mere decoration they were symbols with meaning usually conveying a message. This was the ‘language of flowers’. Common in all ages but embraced with enthusiasm by the Victorians this style of cryprological communication was well understood. There was nothing ambiguous about the message represented by a forget-me-not (remembrance) or of a lilly (purity).

Some of our posy inscriptions are very appropriate and tender, others are quaint and whimsical. An example might be Dr John Thomas, Bishop of Lincoln, who in 1753 who had been previously married numerous times. He has the following inscribed within his last wife’s wedding ring:

If I survive, I’ll make thee five

Many are more deferential, mindful of death and the sermons from the pulpit. The following from 1637: As I in thee have made my choyce, So in the Lord let vs rejoice

In 1931 Joan Evans (sister of Sir Arthur Evans of Knossos fame) wrote a slim but comprehensive volume ’English Posyies and Posy Rings’ and I also recommend ‘Finger-Ring Lore by William Jones, 1898. The following are a few posys I have selected and I hope you find them both insightful and amusing in varying degrees. Many are touching and loving but never pretentious.

Love and feare God

Love and obye

Til’ death us do part

Hearts united live contented

AS GOD DECREED SO WE AGREED

Correct our ways ; Love all our days

My woldely joye alle my trust + heart, thought, lyfe, and lust (English early 16th cent.)

Observe wedlocke ; Memento mori (English 16th cent.)

If you be pleased, my heart is eased (1596)

If you consent, I am conten t (1674)

I have Obtained what God Ordaind

I joy to find a Constant mind

In Christ & thee my comfort be 1744

In thy sight is my delight

In trial trustie (1596)

I bid adieu to all but you

I choose you not in hope to change

I will be yours while breath endures (1633)

Je suis content, j’ai mon desir

Let love abide God will provide

Let love abaide till death devide

Let patience be thy penance

Love me little love me long (1658)

LOVE SERVE AND OBEY

Love’s Delight Is to unite (1674)

No love in life as a virtuous wife

No friendlier recompence than true obedience (1596)

Outward shape, doth reason hate

Sans peur

The Eye finds, the Heart chooseth (1715)

Vnited hearts death only parts (1624)

Virtue and love is from above

We have a Joy None can destroy

Who would have thought it

During my career in jewellery I have made wedding and commitment rings for many couples. They will often request an inscription within the ring, sometimes something cryptic or personal, special to only themselves and to be shared with no other. Often, just initials and a record of the date of the event. If asked what I suggest they might inscribe, I would reach for my list of inscriptions and although ‘no joy in life as a virtuous wife’ might not suit every occasion I hope that young lovers will feel inspired to find something intimate and unique for them in the tradition of the posy ring.

Alistir Tait

BOOK REVIEW

ANDREW GRIMA THE FATHER OF MODERN JEWELLERY By William Grant, 2020.

ACC ART BOOKS,336 pages, 425 illustrations, hardcover, ISBN: 978 1 78884 106 1. £65

“Andrew Grima, the Father of Modern Jewellery” is a beautiful, weighty - yet comfortable to

hold and read - account of the life of Andrew Grima and his jewellery that is perfectly

balanced between text in a clear font and lustrous, very high quality illustrations. There is a

judicious mix of information about, for example, the composition and launch dates of

different collections and descriptions of people, premises and events. The extensive Grima

archive has provided much material that has not been published before. The story begins

with a “Foreword” by Geoffrey Munn OBE, CVO, that sets the scene drawing on his own

knowledge of Andrew Grima and prepares us for the feast that follows. The nine chapters

are divided into sub-sections and there are three “chapters” of images of jewels of three

eras. The book ends with two appendices, a bibliography and acknowledgements.

Chapter I – Family and early life: Born in Rome; The Grima family moves to England; and

The war years. This chapter takes the reader from Andrew Grima’s family and his birth in

Rome through their move to England and his service in the army in Burma. The ups and

downs of this time are handled sensitively and there are occasional hints of the strength of

Grima’s character which were later needed to build his business. The Grima archive

provides photos of the young Andrew and his family, and also images of his early drawings

that demonstrate his artistic talent. There are stories too and we must be grateful that one

hungry Burmese tiger passed by Grima’s tent and continued to the cookhouse such that

next day, in his words, “We had tinned spam and the tiger had baby goat”.

Chapter II – Post-war years and a change of career: H.J. Company; and A new direction. In

“H.J. Company” we learn of Grima’s reunion with Helene Haller who he had known before

the war, their marriage and how he joined a small jewellery manufacturing company, H.J.

Company, owned by her adoptive father. Not being fully occupied by administration, Grima

turned his hand to design and images of some of his early pieces are shown. There are

also details of the difficulties under which the jewellery industry was operating and how

Grima began to develop his own ideas about jewellery. “A new direction” covers the late

1950’s with comments from some of those who worked at H.J. Company accompanied by

photos of them at work and images of examples of jewellery being made at that time.

Chapter III – A new era for British jewellery design: The International Exhibition of Modern

Jewellery 1890-1961; and Prize-winning designs. Much information is provided about the

International Exhibition of Modern Jewellery 1890-1961 giving useful details of how the

exhibition came into being and of some of the exhibitors, that included Grima. A few artists

and sculptors were invited to design pieces for the event. Of these, some had their designs

made up into finished pieces by H.J.Company of which four images are shown together with

one of Grima’s. There is also reference to the competition sponsored by De Beers, the

criteria for which were, “designs should be both experimental and beautiful, frankly

belonging to 1961, which would not have been made at any other time; as uninhibited as

modern sculpture, or fashion; individual, imaginative and smart”. An unfortunate outcome of

the publicity for H.J.Company was a raid on its premises which is recounted for the reader.

“Prize winning designs” sets out how Grima’s company developed after the exhibition and

the role of The Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths in showcasing British jewellery, including

Grima’s, around the world. At this same time Grima entered the De Beer’s Diamonds

International Awards and over the years won 11 International Awards, before joining the

judging panel in 1969 which prohibited him from continuing to compete. The final section of

the chapter is devoted to The Duke of Edinburgh’s Prize for Elegant Design. It was won by

Grima in 1966, the only jeweller ever to do so. The chapter concludes with many images of

jewels that were part of the prize-winning collection and of pieces now in the jewellery

collection of The Goldsmiths’ Company.

Chapter IV – Royal Patronage: Snowdon; and Royal Warrant. The route to Royal Patronage

began after Grima challenged an article in which Lord Snowdon described British jewellery

as “unadventurous”. This led to members of the Royal Family becoming patrons of Grima

and in time to Grima being awarded the “Royal Warrant” by HM The Queen. The images

show pieces of jewellery owned by members of the Royal Family and some of the official

gifts given by The Queen at home and abroad.

Grima jewels of the 1960’s. In addition to the images in each chapter, this and two later

sections provide high quality images of jewellery from these periods. Over 20 jewels from

the 1960’s show a range of the gemstones used and the varied textured surfaces of the gold

wire, bars and rods that are a distinctive part of the design of the pieces.

Chapter V – Grima shops and galleries: Building an international brand. This chapter starts

with an image of Grima’s first shop in London in 1966 and gives details of its design by his

brothers Godfrey and George, its construction and the public’s response. A further shop in

Zurich, managed by Grima’s son Philip, and galleries in Sydney, New York and Tokyo

followed and these too are described.

Chapter VI – Brand collaborations: Dunhill 1965; Omega 1970; and Pulsar 1976. The

account of collaboration with Dunhill has an image of Grima, a pipe-smoker, using one of the

lighters he designed, and painted designs of three further lighters. To see, never mind own,

one of these rare items must be on every Grima collector’s wish list. The collaboration with

Omega begins with its approach to Grima and goes through the designs of the watches

handmade in Gima’s workshop. There are images and details of the gemstones used as the

watch “glass” through which time can be seen for the collection called “About Time”. The

text also includes useful information about further collections by Omega that incorporate

Grima’s designs but were made at the Omega factory. The final collaboration was with

Pulsar for which there is information about the origin of the collection and images of a design

sheet and six of the watches. The author ends by saying, “Grima’s Pulsar collection has

almost ‘unicorn’ status among digital watch collectors; most have heard of their existence

but have never seen one in reality.”

Chapter VII – The Collections: Opal and Pearl, 1970; Rock Revival, 1971; Supershells,

1972; Sticks and Stones 1973; and A Tale of Tahiti, 1974. Each collection is described

separately and accompanied by many images of pieces of jewellery. The descriptions refer

to the inspiration and influences for the collection such as something Grima acquired on his

travels, the availability of particular gemstones, crystals and minerals, or events taking place

at the time. “Opals and pearls” were used in new ways and in unusual settings. “Rock

Revival” was a 100-piece collection based on uncut crystals, rocks and minerals. The

images include a topaz crystal on a “molten” gold chain, an antimony and gold “blackbird”

object d’art and rhodocrosite cufflinks. “Supershells” comprised shells from far away

suspended on a gold collar with a diamond or two, or a wave-like ribbon of tiny diamonds

running along the shell. An Australian pheasant shell became a “seal” with yellow gold

flippers and nose that balanced ruby and sapphire “balls”, and so on. The images must be

seen to be believed. “Sticks and Stones” uses crystals and minerals Grima purchased in

Brazil and Africa. Tourmaline crystals, specularite and dioptase are shown in jewels in this

collection. Lastly, “Tales of Tahiti” is described as challenging the traditional “twinset” role of

pearls in jewellery. The design sketches and images of some finished pieces show

unexpected jewels alongside other different, but less surprising settings for pearls.

The chapter ends with Grima’s comments on business conditions and the challenges facing

British fine jewellery manufacturing. Other jewellers are mentioned, including Tom Scott, a

talented goldsmith, who made pieces of his own design and for Grima. In just a few

paragraphs there is an insight into life in the 1970’s for designers and goldsmiths.

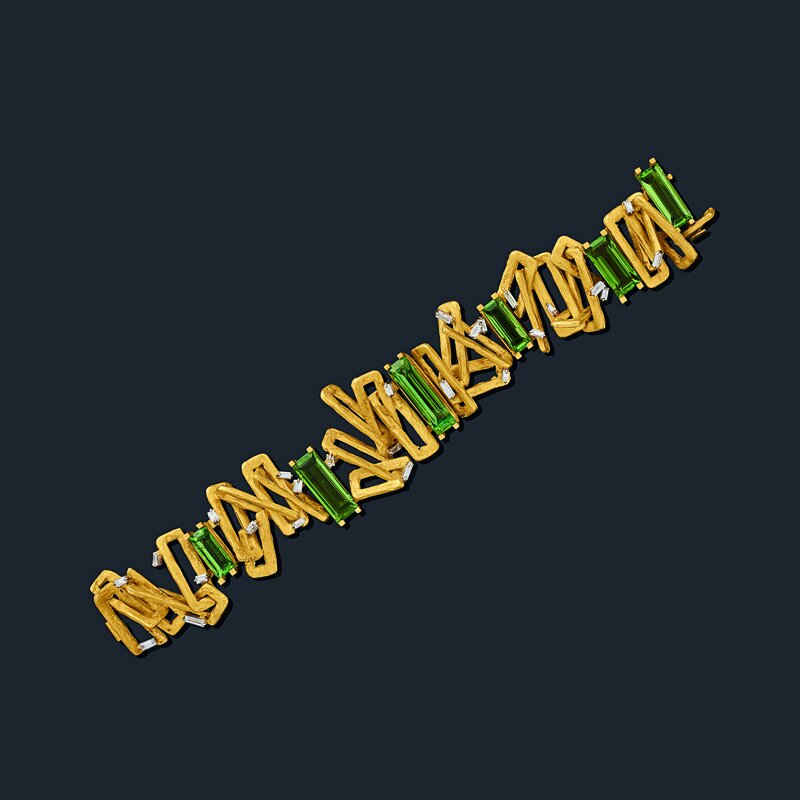

Grima jewels of the 1970’s. Alongside the collections Grima designed hundreds of

individual jewels. They are in platinum as well as gold and have large, more unusual

gemstones, such as kunzite and green beryl, or unexpected pairings such as fire opal with

emeralds.

Chapter VIII – Starting over: Jojo; Life on the road; Casa Farnese; Birth and Rebirth; and

Gstaad. The chapter spans the mid 1970’s to the end of Grima’s life in 2007. It begins with

meeting Jojo, her story, their marriage and life together including much overseas travel and

stays at Casa Farnese, the home where he designed many new jewels. Family life and

business are described from the happy arrival of Francesca to the business problems that

resulted in closing of the shop in London and their move first to Lugano and then Gstaad.

New craftsmen joined Grima and their contribution is given due credit. The chapter is full of

fascinating insights into Grima’s business, his life with friends and the part played by Jojo

and Francesca.

Grima jewels 1980 – 2006. The Grima jewels from this period again show a range of

gemstones such as yellow beryl, moonstone and tourmalines of varied colours, and intricate

metal work. The goldsmiths who were skilled at turning Grima’s designs into jewels,

wearable art, are credited in the descriptions of the pieces.

Chapter IX- Grima’s design philosophy and legacy: The father of modern jewellery; and

Grima today. The influences on Grima throughout his life resulting in his designs and

approach to making jewellery are skilfully drawn together in this very thoughtful chapter and

include some of his own words. Images from the Grima archive confirm his view that a

jewel, “should be as beautiful from the back as the front”. The story concludes with pieces

designed by Jojo and Francesca that have been made by craftsmen who made for Grima or

who learned their craft from those who had made for him. The philosophy of Grima lives on

in these pieces.

Appendix 1: Hallmarks and stamps has useful information that helps to be certain that a

piece is by Grima.

Appendix II: Painted designs provides over 40 images of painted designs

of jewellery and watches from the Grima archive.

The book concludes with a short Bibliography and Acknowledgements.

I highly recommend this beautifully written and presented book. The writing is clear and

illustrations well chosen to complement the text. For collectors, students and anyone who

loves jewellery this is the perfect book to be enjoyed and for study.

Elizabeth Passmore.

Some Grima Designs

Susanne Belperron Book Review

Jewelry of Suzanne Belperron

By Patricia Corbett, Ward Landrigan and Nico Landrigan, 2015, Thames and Hudson Ltd, London, 239 pages, ISBN 978-0-500-51790-1. £50 hardcover

“Jewelry of Suzanne Belperron” provides a beautifully illustrated record of her life and work. The book repays the effort of reading the extensive text. There is a large number of illustrations including gouache paintings and tracings from the Belperron archive of designs and photographs of finished jewels.

The first eight unnumbered pages provide a useful introduction. The images of jewellery indicate the high quality of all the illustrations and the photo of Belperron wearing some of her own jewels makes clear the size of her jewellery; and the book’s title is expanded with the significant quotation, “my style is my signature”. The notes on page 6 are helpful in following the career of Belperron and knowing who she worked with to realise her designs.

Images of some of Karl Largerfield’s personal collection of Belperron jewellery accompany his forward to the book and the four-part preface is written by Ward Landrigan, Nico Landrigan, Jean Herz, and David Herz. There are five “chapters”: Coming of Age; Maison Boivin and Art Deco; Maison B Herz; The War Years; and A New Partnership.

“Coming of Age” opens with a reference to one of Belperron’s patrons in 1936, “the King of England” and then reverts to describing the first 18 years of her life. Born Suzanne Vuillerme on 26 September 1900, we learn of the local cottage industry of lapidiares, that included her ancestors, “supplying rock crystal, precious and semi-precious stones to goldsmiths and watchmakers in nearby Geneva”. There is much detail about her early life leading up to her enrolling in 1916 at the Municipal Schools of Music and Fine Arts in Besancon for the course in “industrial design for jewelry, metalwork and objects d’art”. Images show the influence of local architecture and the materials available, for example, rock crystal and chalcedony, on her later jewellery. In 1918 she won the completion organised by the Besancon fine arts commission for her watch pendant in yellow gold with black and white champlevé enamel.

“Maison Boivin and Art Deco” begins with Belperron’s move to Paris in 1919 for her first paid employment. She also attended free studio classes for women at Ecole National des Arts Decoratif and it is thought that through these classes she became acquainted with Madame Jeanne Boivin who had been running Maison Boivin since her husband’s death in 1917. A brief history of Maison Boivin is set out. The authors suggest that perhaps Maison Boivin recognised Belperron’s innate flair in choosing her to be the designer-draftswoman for the House. In 1924 she married her fiancé Jean Belperron, and in the remaining chapters there are occasional references to him and to their private life.

The chapter traces the change in style of Maison Boivin and records Vogue Paris December 1928 as having four photographs of Boivin jewels that show “Suzanne’s inimitable style”. Items in the Boivin catalogue were not ascribed to Belperron until recently, but it is said that her idiosyncratic draftsmanship enable her renderings to be easily identifiable. Distinctive features of Belperron’s work are described and illustrated. The large number of images and the relevant text are not always immediately adjacent, but having so many images greatly outweighs any effort needed to link text and images. Occasional references to Belperron’s ways of working, such as how she chose the stones to use in her pieces, should resonate with gem and jewellery enthusiasts.

“Maison B. Herz” In 1932 Belperron joined Bernard Herz, a premier diamond merchant and perlier. Speculation on the reason for her move is discussed and it is noted that she had added to the company (Boivin) records to indicate her designs suggesting that a desire for due recognition was a factor. She did not sign her jewellery saying simply “my style is my signature”. This chapter, more than twice the length of any other, records something of the history of Herz and also of Grone & Darde who executed Belperron’s designs. Most of the chapter provides detailed text about a wide range of jewellery and is accompanied by many images of designs for jewellery and jewels, and images of the jewels being worn by their famous owners.

“The War Years” This relatively short chapter describes the impact of the second world war on Belperron and those close to her, notably the Herz family and includes her takeover of the Herz firm to become Suzanne Belperron SARL in 1941. The production of jewellery continued and images show designs a little different from and lighter than earlier pieces.

“A New Partnership” refers to the new firm of Jean Herz-Belperron founded after the war. The story of this firm is described and the many images of Belperron’s jewellery show once again her use of a wide range of gems in jewellery of all types. The business closed in 1974 and the chapter continues with details of Belperron’s life in retirement up to her death in 1983. It concludes with references to jewels sold at auction and images of glorious jewels.

Finally the book concludes with an epilogue which touches on current developments concerning Belperron designs, an extensive bibliography, photographic credits and acknowledgments. I recommend this book.

Elizabeth Passmore

‘The Silversmith’s Art – Made in Britain Today’

An Exhibition at the National Museums of Scotland, Edinburgh

‘The Silversmith’s Art – Made in Britain Today’

An Exhibition at the National Museums of Scotland, Edinburgh

This exhibition comprises a collection of silver produced from the year 2000 until the present day, it represents the latest chapter in the current cycle of the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths’ external exhibitions. The 66 silversmiths featured in it represent the artistic range of talent in Britain today. Significantly, 33 are women where in the past the craft was mostly dominated by men. Perhaps, more remarkably 18 come from abroad and reflect very different cultures and traditions.

Their range of work is exceptional, diverse and highly creative. The Goldsmiths Company is the principal patron of the silversmiths art in Britain today highlighting an age old tradition in a very modern way. Today, most British silver manufacturers outsource production to the Far East but the silver displayed within the exhibition hall demonstrates that hand-made craft and studio silverware survives, perhaps by the skin of its teeth but certainly with tenacity.

The display is simple with all the focus on the objects. There are old friends here, Malcom Appleby has several items. His ‘Millennium Casket’ is one of the first things you see when you enter the room. It is embossed with a rising and setting sun symbolising the passage of time throughout the seasons and a large moonstone cabochon (something for the gemmologists) is evocative of the moon’s influence on tides enhancing the imagery of the fundamental elements of life.

Another Scottish workshop represented is that of Adrian Hope, a graduate of Edinburgh College of Art. ‘Preciousness is a hindrance’ he says ‘Usefulness a happy bonus’. There is a ‘snow’ bowl and a ‘snowcord’ vase. Subtle and beautiful.

In each artefact displayed we see a reflection of the designers view on life and personal philosophy. Each item is intensely personal. I think my favourite piece is ‘Deluge Dish’ made by Mirian Hanid in 2009. This piece is an enormous slab of silver almost a meter long. Miriam is inspired by the movement of water and her piece evokes the ebb and flow of Atlantic waves breaking on the coast. Hand formed with wooden hammers using the age old skills of repousse’ and chasing she creates a flowing rythmn of wave like forms.

Please don’t miss this exhibition. It is open until the 4th of January and is featured in the building that we all used to know as The Royal Scottish Museum – what ever happened to the ‘Royal’? Entry is free but I wonder why such a wonderful exhibition is hidden away in an upstairs gallery and not situated in a more significant and accessible part of the building. There is a book to accompany the event, at £12.99, less if you are a member of the museum.

In addition to the images featured below, the following page gives a fuller selection. <http://thesilversmithsart.co.uk/exhibitors/>

OBITUARY

Catriona McInnes M.B.E. M.A. F.G.A was known to all who knew her, as the smiling, welcoming face of the Scottish Gemmological Association.

After gaining a degree in Politics & Economics, Catriona trained as a mathematics teacher, but it was when she joined the Glasgow Geological Society in the early 70’s that she took a keen interest in geology, returning to university in 1976 to do a degree in the subject during which she helped catalogue mineral specimens for the Hunterian Museum.

She met her husband John on a fieldtrip and they soon married in 1977. They moved to Edinburgh in that year for John’s work at the now “ British Geological Survey”. Catriona continued teaching in secondary school where she developed the course for the new subject of computer studies gaining her an M.B.E. in 1996 for her services to education.

All their spare time and holidays, along with their children and dog, were spent collecting minerals and gemstones. They visited many localities described by M. Foster Heddle in “The Mineralogy of Scotland” and have amassed an immense collection of Scottish minerals earning them a worthy and detailed mention as private collectors in “The Minerals of Scotland Past & Present” by Alex Livingstone.

Once the family grew up, they focused their holidays around visits to famous mineral localities in many parts of the world, both buying and collecting gemstones. Catriona did her Gemmology Diploma in 1997 and afterwards taught gemmology at the University as well as doing practical tutorials for Gem A students in Scotland and Northern England.

She set up her own business collecting and selling gemstones with a speciality in Scottish Gemstones. Sapphires from Lewis and Mull, Smokey Quartz from various areas in the Cairngorms, Prehnite from Loanhead Quarry Ayrshire, Garnets from Elie Fife and Tourmaline from Glenbuchat among a few.

Previously, Scottish students attaining their F.G.A. became members of “Eggs” Edinburgh Gemmology Group run by Brian Jackson but as the popular group was restricted in numbers due to its accommodation so there was no room for the newly qualified F.G.A’s to join and continue their passion. Catriona with the help of friends resurrected the Scottish Branch of the Gemmological Association of Great Britain to encourage an interest in gemmology in Scotland. She took over the organisation of the annual conference in 1999, which went from strength to strength with her great enthusiasm and superb organisational skills making everything run like clockwork, allowing delegates time for fun as well as knowledge.

The S.G.A. was founded in 2008, Catriona was one of the five inaugural members and became the most wonderful secretary any organisation could have wished for. She helped established the S.G.A. Conference as the friendliest Gemmological Conference Worldwide.

Scottish Gemmologists have lost their shining star and special friend. She had a smile and kind word for everyone, giving of her time and enthusiasm so freely. We will all miss her and cherish her memory.

This article first appeared in Gems&Jewellery, July 2015. Composed by Gillian O'Brien and reprinted with permission from The Gemmological Association of Great Britain, Gem-A. <www.gem-a.com>